ManEVesto 2024: EV Charging Policy for the New UK Government

The UK has suddenly been thrust into a general election, leaving question marks over the country’s EV charging policy as existing legislation may be overturned in party manifestos and a different electric vehicle industry dynamic may appear for the next administration.

It’s also clear that there’s been a recent slowdown in EV sales in the United Kingdom and other Western markets.

The Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT) which publishes monthly updates and analysis of vehicle sales, has been highlighting the lack of incentives for the EV transition – in particular, the need to reduce VAT on public charging points.

The Fully Charged Show has been spearheading the Stop Burning Stuff campaign with former Top Gear presenter Quentin Willson. They are providing resources, including the Little Book of EV Myths (written in conjunction with the RAC), the Charging Charter, and Fair Charge.

Fair Charge has been asked to give evidence at parliamentary hearings over EV policies.

ManEVesto: Versinetic's EV Charging Policy

Therefore, here at Versinetic, we’ve compiled a ManEVesto – several initiatives that would address both the shortcomings of existing policies while serving the needs of the transition to alternative fuels, zero emission vehicles & clean transport (namely, EVs) and the public interest.

These policies are all intended to:

- benefit the economy

- provide greater accessibility

- and improve communication and public confidence.

The initiatives all have different costs vs benefits, alongside implementation timescales.

What are the key components of an effective EV charging policy?

Investment in a comprehensive network of EV charging stations for public spaces across the country, including both fast and rapid chargers.

This will help ensure that there are enough charging options available and reduce the worry about running out of power while on public roads.

Providing incentives or subsidies for installing EV charging points at homes and workplaces can make charging much more convenient for EV owners. Imagine being able to charge your car while you’re at work or overnight at home – it would make owning an EV so much easier.

All the different charging networks and EV models must be compatible with each other.

Adopting standardised charging protocols and connectors helps ensure you can charge your car at any station without compatibility issues – making this an essential component of any EV charging policy.

Greater financial support – for instance, reduced electricity rates for EV charging, tax credits for EV purchases, or reduced parking fees for EVs—can make owning an electric vehicle more attractive and affordable.

Regulations to maintain pricing for EV charging services that is fair, transparent, and competitive.

This helps prevent overcharging and promote consumer confidence in the EV charging network.

Integrating EV charging infrastructure with public transport hubs, like park-and-ride facilities, promotes the use of multiple modes of transport and reduces overall vehicle emissions.

Investing in the research and development of advanced EV charging technologies, such as wireless charging or battery swapping, can help improve the efficiency and convenience of charging infrastructure in the future.

ManEVesto 2024

According to Zap-Map[1], there are approximately 33 charging networks in the UK, most of which have their own charging app.

This doesn’t include the large number of local networks. For some fast and most rapid chargers, it’s possible to use a debit or credit card, or Apple/Google Pay for charging sessions.

But EV drivers frequently require downloading multiple apps; providing repeated personal details and then often having to pre-pay £10 or £20 to use almost identical contactless payment mechanisms; for networks they may only use once.

In a mature industry, this would be unacceptable. This leads to:

Declaration 1: The new government could and should mandate a single, Universal EV Charging Payment app [UVCP]

This EV charging policy would allow development costs amongst networks to be pooled while providing consistency and accessibility, especially in charging locations where the signal is too poor for downloads.

Specialised features could be provided via plug-ins, and charging itself would be directed to the appropriate provider.

Net cost: negative: charging networks can share the funding and save money while new charging companies are incentivised to enter the market.

and also leads to…

Declaration 2: EU rollout - Make the UVCP pan-European

The same benefits apply at scale for a potential 500 million customer base as for a 65 million customer base.

This would also help improve relationships with Europe while benefiting from common goals.

Net cost: negative, though there will be some up-front investment involved to coordinate with European bodies.

Declaration 3: Regulate public EV charging costs

Pricing regulation works for fossil fuels and should be adopted as an EV charging policy.

VAT should be reduced to 5% as per calls from Fair Charge and SMMT.

In addition, since wholesale and domestic electricity is cheaper than fossil fuels, public charging should always be no more than 60% of the cost of fossil fuels.

Net cost: about £71m for the VAT reduction, just 1% of the cost of the 5p reduction in fuel duty.

Maintenance

Public charging points have maintenance issues for several reasons.

Unlike fuel stations, across the UK’s EV infrastructure most charging points aren’t manned, therefore it’s harder to detect faults and respond to them.

In addition, the industry is still relatively new, with rapid technology improvements leading to software maintenance challenges. There is also a manufacturing learning curve – for example, user-interface water ingress.

Current government policies have been fairly punitive: large fines for minor failure rates.

Making it easier for companies and local authorities to maintain their electric vehicle supply equipment, or EVSE, would be better.

Pricing regulation works for fossil fuels and should be adopted as an EV charging policy.

VAT should be reduced to 5% as per calls from Fair Charge and SMMT.

In addition, since wholesale and domestic electricity is cheaper than fossil fuels, public charging should always be no more than 60% of the cost of fossil fuels.

Net cost: about £71m for the VAT reduction, just 1% of the cost of the 5p reduction in fuel duty.

Declaration 4: UK Customer Support Network

Introduce the national equivalent of the AA or RAC for charger support.

A significant EV charging policy that would avoid the duplication of multiple helplines and mean all EV users can be supported 24/7.

Call support staff can follow scripts tailored to the charger provider related to any actual maintenance issue.

Net cost: significant in the development stages, but beneficial in operation, by optimising resources. A high proportion of costs could be delegated to the network operators themselves.

Declaration 5: Chargepoint Maintenance Subcontractors

Introduce the national equivalent of the AA or RAC for charger support.

A significant EV charging policy that would avoid the duplication of multiple helplines and mean all EV users can be supported 24/7.

Call support staff can follow scripts tailored to the charger provider related to any actual maintenance issue.

Net cost: significant in the development stages, but beneficial in operation, by optimising resources. A high proportion of costs could be delegated to the network operators themselves.

Accessibility

Nearly 40% of UK households (9.5 million) don’t have access to off-street parking, which represents a serious constraint on EV adoption.

Including on-street, shared parking and other residential solutions, accessibility could be as high as 77%, With a 1:3 driver-to-charger ratio the UK will have to install 3.9 million off-residence chargers.

Although this sounds daunting, there are already close to 1 million domestic chargers installed in the UK for our existing registered EVs and another 6 to 9 million or so on-residence chargers will be installed privately by around 2030.

The demand for the remaining on-street charging installations is likely to be later adopters, for the same reason that they use predominantly cheaper accommodation.

But we still need an EV charging policy to adequately address the issue. How can we do it?

Declaration 6: Accessible Charging Programme: Street-level

Greater rollout of On-Street Residential Chargepoint Schemes – ORCS), such as:

- Gullies allowing charging cables to reach streets

- Conventional street-installed chargers

- Chargers installed in lamp-posts (no extra obstacles and cabling and conduits are already available)

Initiatives like Connected Kerb providing kerb-based, and rising charging points.

Net cost: about £1K/installation for 4.2m houses = £1.4bn.

Declaration 7: Accessible Charging Programme: Communal

Communal parking for apartment blocks is fairly common.

An EV charging policy that provides incentives for their managers and owners to install smart charging points has an obvious appeal, because they will be easier to manage; will make accommodation more desirable, and may provide a source of revenue.

Net cost: about £560m.

Declaration 8: Accessible Charging Programme - UVCP

Because UVCP would be a universal app that integrates with charging providers, there’s no reason why it can’t be used to provide on-street charging, local to residents, sourced from their energy providers, at their prices.

In addition, there’s no reason why the same mechanism can’t be pack-ported to already installed, domestic EV chargers.

They could be configured as part-time, public chargers with the owners’ consent and a suitable reward scheme.

Net cost: £1m for software development and £300m/year by 2050 for a given charger’s host[3].

Declaration 9: Accessible Charging Programme - Energy/Parking Stations

It’s possible to replace one or two houses in congested streets with combined parking, charging facilities, security and V2G backup.

Here, there is a net benefit in reduced parking congestion, but building costs are high.

Net cost: an average of £253K per terraced house[3] + upwards of £300K per conversion, or about £550m per 1000 streets.

Declaration 10: Ridesharing

Accessibility doesn’t necessarily mean owning an EV.

A government EV charging policy that makes ride-sharing more easily available to individuals in many cases (particularly those in rural communities with less public transport access), should be possible if safeguarding issues can be addressed via Smartphone apps.

Net Cost: probably in the range of £10m to £20m for app development due to the extra safety testing required.

Declaration 11: EV Public transport

EV public transport across the country is happening at a municipal level. However, an EV charging policy featuring a national programme for cleaning up public transport could accelerate deployment while lowering sustainability costs for councils and users.

Due to lower fuel costs, it would also provide the opportunity to use vehicles in V2G mode during off-peak hours, as happens with some bus services in the US[13].

Net Cost: About 900 coaches are bought annually out of 28000 UK coaches so the up-front costs are offset by better than half the fuel costs.

Charger installation represents a significant cost but is also incremental because investment only needs to track EV adoption, and that will only likely reach about 50% by 2030.

Thus the estimated yearly cost between 2025 and 2030 ignoring Declaration 8 would be (£1.4bn+£560m+£150m) x 50% / 5 years, which is a mere £211m per year (approximately £8.60 per household per year).

Affordability

While the issue of charging is a significant worry for potential EV users, the primary hurdle at present, as consistently emphasised by SMMT, is the cost.

An obvious mechanism is to draw from the UK government’s Affordable Home Ownership Schemes[4], which is a fairly wide and comprehensive set of policies for enabling home ownership.

Admittedly, market discounts are unlikely to apply, because they are similar to EV grant schemes in previous years, and these have gradually been phased out across the UK and EU.

Yet other mechanisms within this programme could apply:

Declaration 12.1: The home-ownership model, shared ownership

The reality is that most cars are only used for a small fraction of each day, so the potential exists for drivers to share the ownership or usage of an EV like a car club.

This way, an EV could meet most of their needs while shared fossil fuel cars serve as backup.

Making this work requires changes to insurance law and, importantly, logistics applications to maximise EV availability.

Net cost: legal changes would be low; lower insurance capital and potentially less investment in cars per se would likely lower GDP.

Declaration 12.2: The home-ownership model, loans and PCP

One of the easiest mechanisms to extend EV ownership is through loans and PCP.

Both mechanisms can offset the current higher costs for EVs by enabling their drivers to benefit from the lower running costs.

A loan or loan/PCP scheme differs from salary sacrifice or grants by applying to lower-income drivers and second-user vehicles so that the lower running costs serve to pay back the interest on the loans.

Net cost: supporting 1 car for the 3rd to 6th deciles [14] with a 3-year £1800 loan for a total of 7 million cars would peak at £12.6bn of loans.

This would represent an ownership cost of £50/household for these households per month.

Declaration 12.3: The home-ownership model, Key Workers

The definition of key workers was wide during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Some are still considered eligible, particularly health workers such as Community or District Nurses, who received a one-off payment this year[5] up to £3000.

However, most key workers have second-user cars, which means the net cost could be the average of a low-end EV minus the average second-user car price, or about £16K.

Net cost: about £16K x 4000 nurses over 5 years = £12.8m/year.

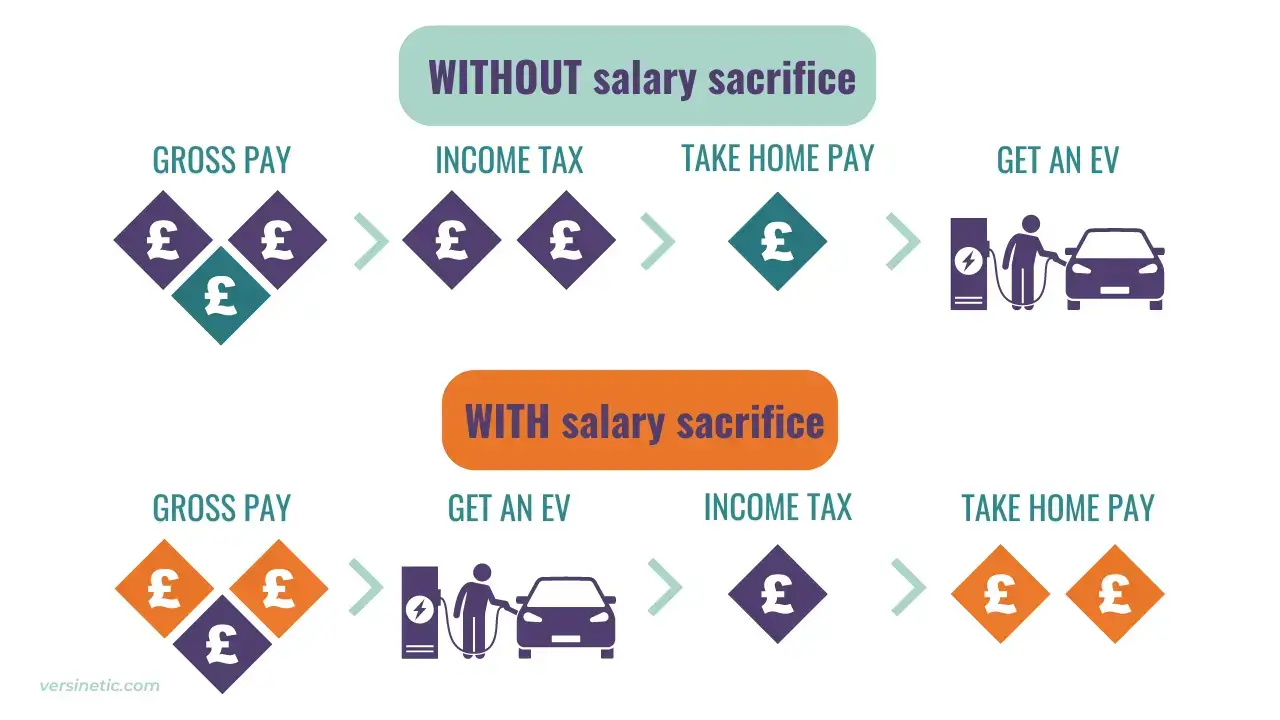

Declaration 13: Salary Sacrifice

Changing the law and updating the UK’s EV charging policy to make Salary Sacrifice available as a default option for employees would effectively lower new EV costs.

For example, a salary sacrifice of £200/month saves £40/month, equivalent to a PCP £40 higher; enough to make driving an e-Corsa £60 cheaper per month than the petrol equivalent while EVs are more expensive.

Assuming EVs reach price parity by about 2030, and half of the new cars sold between now and 2030 are EVs where the owners save £60/month, the Net Government cost is: (2030-2025) x 1 million cars x £60 x 12 months = £3.6 billion per year.

To put this in perspective, that’s less than the 5p cut in fuel duty.

Declaration 14: Insurance

The current evidence shows that electric cars have fewer accidents, and are more reliable than combustion cars. But EV insurance, particularly for new drivers, is more expensive due to the immaturity of the market.

Importantly, because surveys of younger drivers show they are more open to EVs, incentives to support younger drivers would be helpful.

Regulating EV car insurance to match combustion vehicles underwritten by the government would provide more confidence for the insurance industry and should have a negligible net cost.

Declaration 15: ICE/EV Price differentials

Leading zero-carbon technology website CleanTechnica [8] estimates that because LFP batteries now cost around €49/kWh, and an EV drivetrain is €2000 in quantity, a low-end EV shouldn’t cost €4K more than the petrol equivalent.

A UK government could update the ZEV mandate to prioritise lower-cost EVs.

This could be done, for example, by increasing fines for non-compliance based on an average selling price, or by increasing higher-end EV penalties.

Net cost: relatively low, because VAT on more, but cheaper EVs could more than balance the revenue from high-end EVs and EV sales non-compliance.

Declaration 16: The Second-user EV market

Most people still buy EVs new because the growth rate is high and the market itself is new; whereas most combustion cars, 80% to 90%, are bought second-user.

One way around this problem is to make it easier to inject second-user cars into the market, by making it easier for fleet buyers to buy EVs.

It makes sense to fleet buyers because they can price in the Total Cost of Ownership more easily than private buyers.

Perhaps combining fleet purchases with Salary Sacrifice schemes could work, accelerating a purchasing trend we’re already seeing in the UK.

Drivers get a cheaper EV than they otherwise would, paying at similar rates as fleet, while fleet get additional discounts from more mass purchasing.

This, in turn, accelerates the second-user market after the lease period.

There is the risk of an EV economic bubble which would have to be managed. Although of economic benefit to users, this is likely to be more of a legislative issue – and may even be a net economic gain due to industry growth.

The Net-Zero Economy

Clean transport goes hand in hand with the Net Zero Economy, both from a practical viewpoint (we are committed to Net Zero transport by 2050), but also from a public perception viewpoint (cleaner energy generation makes it easier to argue for electric vehicles).

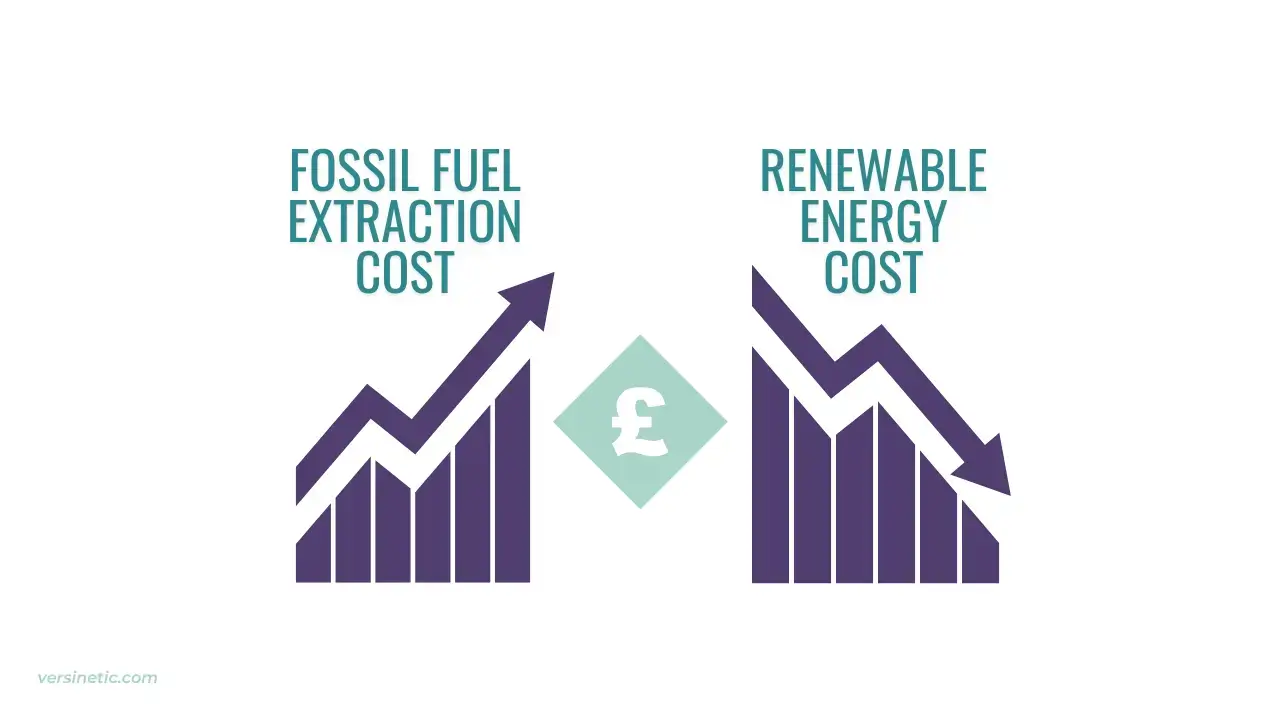

Declaration 17: Renewable energy for cleaner transport and lower energy costs.

Renewable energy is getting 15% cheaper each year, while fossil fuel extraction is getting more expensive (adjusting for global market decisions).

EV owners can benefit from cheaper charging at off-peak hours; and reduced energy costs by private, commercial or community-shared renewable energy ownership.

Government incentives for private renewable energy could be resumed and managed at a reasonable GWh per year.

Current costs are about £2K for 4kW of Solar PV, falling to about £1K by 2030.

Declaration 18: Accelerated battery manufacturing

This EV charging policy would:

- help the UK economy by providing new jobs

- help lower the domestic cost of new batteries in the UK

- provide an additional export market

- support a future industry for replacement EV batteries of the kind undertaken by Cleeverly.co.uk[12].

Battery manufacturing is a critical industry and requires real support to avoid a repeat of the BritishVolt debacle[15].

Declaration 19: EV Manufacturing

Although Nissan in Sunderland and JLR helped pioneer the introduction of early EV manufacturing in the UK, we have subsequently fallen behind.

It should be possible to re-ignite manufacturing and development for both private and public transport.

Furthermore, the EU is likely to introduce additional tariffs for Chinese EV manufacturers.

This might be an instance where Brexit may benefit the UK, by being able to shift the assembly or manufacturing of Chinese-licensed EVs onshore. These could be sold to the EU with reduced tariffs.

An obvious manufacturer for this is MG, whose MG ZS-EV, MG5 and MG4 series of rebadged Chinese EVs have become very popular.

Declaration 20: Support for ULEZ and CAZ initiatives

Although 90% of current vehicles are covered within ULEZ and CAZ style clean-air charges, additional costs for the 10% of business and private vehicle owners who couldn’t afford to comply was a frequently-raised complaint.

Yet, clean air should be a popular policy, with polluting cars ultimately becoming as socially unacceptable as smoking in public buildings.

National-level mechanisms for making sure these groups are never worse off by such schemes would be valuable, both for when ULEZ and CAZ are progressively tightened during the late 2020s and 2030s, but also to serve as a model for popularising and extending clean-air measures across the country.

By updating its EV charging policy, the new UK government could implement a salary sacrifice investment program. This program would help users save money to cover any additional costs they may incur. The program could also include scrappage schemes.

Net cost: minor, possibly negative. As a salary sacrifice-type scheme, members lose an untaxed proportion of income, which the government gets to use for public investment over the period.

Conclusion

Only a few initiatives are likely to make it into the government’s EV charging policy. However, the large number of potential initiatives shows how much scope there is for accelerating EV adoption within the UK.

Policies can range from simple VAT changes to income-tax adjustments to information technology and also from policies that span EVs themselves to charging infrastructure EV manufacturing and ultimate Net-Zero goals.

Also, the measures proposed tend to be beneficial to most income levels without penalising any income level and are complementary rather than exclusive. This means that some policies could be applied quickly while others would help provide a vision and legacy across multiple parliaments.

Ultimately, they are comparable to the pioneering work in phasing out new combustion cars by the first half of the 2030s and the cross-party, 2023 ZEV mandate to ensure a managed transition towards zero emissions.

Each of these can be placed somewhere on a national benefit/cost matrix and although some may be more appealing to one political party than another, and some are certainly more feasible than others, there are some amenable to parties across the political spectrum.

Ultimately, the transition to clean transport is a beacon of hope for the 21st century. EV adoption is temporarily slowing in Europe and the US due to the headwinds of misinformation and a cost-of-living crisis.

Nevertheless, few people actively want to live in a polluted environment and for the rest of us, the transformation represents both an exciting challenge and an inspiration for what we can become in the decades ahead.

Further reading

[1] https://www.zap-map.com/ev-guides/public-charging-point-networks

[2] Assumes a remainder of 3.9 million households driving 15 miles per day at 3.5 miles per kWh with a subsidy of £0.05/kWh.

[3] https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-house-price-index-for-january-2023

[4] https://www.gov.uk/affordable-home-ownership-schemes

[5] https://www.gov.uk/government/news/one-off-payments-of-up-to-3000-for-over-27000-health-workers

[6] https://www.nimblefins.co.uk/cheap-car-insurance/average-cost-cars-uk

https://www.nimblefins.co.uk/average-cost-electric-car-uk#nogo

[7] PCP e-Corsa (£281) vs £205.

https://www.vauxhall.co.uk/cars/new-corsa/offers-finance/electric/latest-offers.html

https://www.fuelly.com/car/vauxhall/corsa

[9] https://www.statista.com/statistics/300887/number-of-buses-in-use-by-region-uk/

[10] https://www.zemo.org.uk/assets/reports/LowCVP%20Coach%20report%202020%20web%20version%20V2.pdf

https://www.transportengineer.org.uk/content/features/on-a-charge-the-economics-of-electric-buses/

[11] https://www.offgridsolarsales.co.uk/bulk-pv-panels-5-units

[12] https://www.cleevelyev.co.uk/battery-upgrades/

[14] ons.gov.uk

Julian Skidmore is Versinetic’s EV Industry Analyst.

He has a Computer Science degree from UEA and an MPhil in Computer Architecture from Manchester University, as well as over 20 years of experience in embedded systems development.

As a senior software engineer, Julian has worked on EV charging and V2G projects, and has also co-authored EV-related articles for the electronics industry press.

Julian is a proponent of the zero-carbon society and a Guardian News ‘climate hero’. He has owned a battery EV for over two years, has investments in wind farm cooperatives, and has a 4KW domestic solar PV installation.